Born in Lebanon in 1968, playwright Wajdi Mouawad fled to France between the ages of ten and fifteen , before living in Quebec until 2000. His adaptations and stagings of classical and contemporary plays, as well as his own texts, have been translated on all five continents. Over the years, this self-taught artist has built up a solid literary culture through the stories of famous writers, particularly French ones.

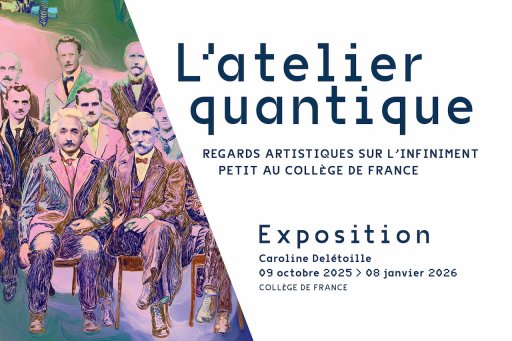

In 2024, at the invitation of the Collège de France, Wajdi Mouawad will hold the The Invention of Europe through languages and cultures Annual Chair, created in partnership with the French Ministry of Culture. An opportunity for the playwright to question his relationship with writing and the mechanisms behind creation.

Wajdi Mouawad's entire life revolves around writing." I think all day long about what I could write, there's nothing else that interests me. Even when I sleep, I think about it. I don't know if I know how to do it well, but I don't know how to do anything else ", admits the actor and playwright, whose prolific body of work has been translated into over twenty languages. Over the course of his career, Wajdi Mouawad has acted in adaptations and stagings of classical and contemporary plays, as well as his own texts. He has also acted under the direction of other artists such as Stanislas Nordey, in France in 2010, in Les Justes by Camus or in Le Pays rêvé by Jihane Chouaib and recently in Justine Triet's feature film Anatomie d'une chute and Chloé Mazlo's Sous le ciel d'Alice. Since April 2016, he has been director of the Théâtre de la Colline, one of the five théâtres nationaux along with the Comédie-Française. Quite a revenge for this son of Lebanese immigrants, who had no command of the French language when he arrived on French soil at the age of ten to flee the war.

Literature as a mirror

Wajdi Mouawad's relationship with writing began in adolescence, around the age of fifteen , when he wrote his first texts. But the roots of the young boy's affinity for artistic forms of expression go back much earlier. In Lebanon, he was already drawing and painting a lot." I didn't start talking until I was seven. Drawing and painting were a way of expressing myself without having to speak. " It was in the small apartment he occupied in France, his host country from 1978 until 1983, that the switch to literature took place. The young Wajdi began reading books, such as the adventures of Bob Morane. He also dipped into his older brother's library and began reading more " serious " books for his age, such as Franz Kafka' s Metamorphosis. In this short story, written in 1915, a young salesman, Gregor Samsa, wakes up one morning to discover that he has been transformed into a gigantic insect. This marks the beginning of a troubled period for the hero, who is cut off from the outside world and his family, who remain deaf and indifferent to his inner suffering.

At the time, the young Wajdi felt " out of step " with his classmates, something he discovered he had in common with the hero of The Metamorphosis. He continues : " I wanted to be Bob Morane, but all I had to do was look in the mirror to realize that I didn't look like him. Bob Morane was the hero I wanted to be, but would never be. Kafka's hero, Gregor Samsa, was just the opposite, and his story acted as a mirror for me. " His discovery of literature continued at school, where he discovered the works of Victor Hugo, Arthur Rimbaud and Molière. His first play was Molière's L'Avare. He played the play's hero, Harpagon, in front of the entire class. To play him, the young Wajdi was inspired by the comedian Louis de Funès, a man of flamboyant good looks and explosive character. Quite the opposite of the shy young boy he played to others at the time." I'd prepared everything meticulously and memorized the text. It must have had an effect on the other students, because after that performance, their outlook changed. It was from this experience that I realized that through literature and art, it is possible to change things, to develop a form of self-regard. " However, he doesn't yet see himself as a writer : " when you read these works by great authors, you tell yourself that before you can write, you must already know the beginning and the end of the story. But this thought is overwhelming for the mind, it makes the act of writing unthinkable, even if in reality it's not true. "

Writingto repair wounds

Wajdi Mouawad's childhood shaped him as an artist, insofar as he drew much of his later inspiration for his work from it. When he arrived in Canada, he joined the National TheatreSchool, somewhat by chance, " because I read that you didn't need to have a high school diploma to apply ". It was there that he wrote his first play, at the age of twenty ." Iwas studying Shakespeare and Chekhov, but that wasn't my story. So I decided to write this story, which was not only mine, but that of thousands of other Lebanese. " He chose to tell the story of a boy in exile. Since Quebec, too, has a history of exile, due to its special situation with Canada, it has met with great success locally. Quebecers are not the only ones touched by this story. For Lebanese exiles, it echoes their own experiences, and they let the author know, who would continue to be inspired by the theme of exile and war throughout his career.

In 1991, with director and actress Isabelle Leblanc, he co-founded his first company : Théâtre Ô Parleur. Then, at the helm of Montreal's Théâtre de Quat'Sous from 2000 to 2004, he created Incendies, a dramatic work exploring themes of identity, memory, violence and family secrets, which was adapted for the screen by director Denis Villeneuve in 2010. Inspired by her biography, the play is set against the backdrop of a civil war reminiscent of Lebanon, and tells the story of twins Jeanne and Simon, who receive the last will and testament of their recently deceased mother. They embark on an unexpected quest that takes them on a journey to the Middle East, where they discover their mother's painful past. A work in which Wajdi Mouawad depicts the devastating impact of war on individuals and families, the weight of family secrets and the impact of trauma on descendants.

A form of therapy

Indeed, the playwright remains convinced that literature can help resolve conflicts, reconcile and even repair." Iwas a victim of the war for four years, then went into exile. I witnessed the silence of my parents and adults in general. I saw what the war did to them. I experienced political silence, where politics was never addressed head-on. The work that post-war Germany did on itself, Lebanon never did ". For him, writing is not just a cultural act." There's something else behind it. We need to tell our story, it's also an act of dignity and recognition. " The power of literature lies not only in the power of words, but also in the imagination." It is the imaginary that creates distance, frees the spectator from his or her discomfort " and, in short, offers a quasi-therapeutic outlet in the sense of what Wajdi Mouawad describes as " catharsis ". First introduced into Western literature by the philosopher Aristotle, catharsis refers to a process of emotional release, experienced by the viewer or reader, through a work of art. It's this feeling that the playwright seeks to reproduce in the spectator, by inviting him or her to follow the story of characters whose lives are ordinary, but whose journey echoes a form of universality in which everyone can recognize themselves.

For Wajdi Mouawad, literature is not only an outlet, but also a way of describing the inconceivable, of touching a form of truth. It is perhaps in this quest for the "true" that science and literature come together, says the playwright. Science and literature, each in their own way, attempt to reach " that moment when we are beyond reality, which is truer than reality itself "." There is the real and the true. And the real is always more powerful, because it allows us to extricate ourselves from appearances. " He acknowledges, however, that the paths taken by artists are different from those chosen by scientists. The scientist seeks to grasp the truth through knowledge. The poet, on the other hand, tirelessly seeks to extricate himself from all forms of certainty." Not that he is against knowledge, on the contrary, but obstinately, stubbornly, the poet seeks to keep inaccessible a fragment that has always eluded knowledge ", he writes. Where the scientist tries to explain by referring to protocols, calculations and method, the poet uses words and metaphors." My tool is the pencil ", he notes.

Teaching at the Collège de France

At the invitation of the Collège de France, Wajdi Mouawad will this year hold the The Invention of Europe through languages and cultures Annual Chair, created in partnership with the French Ministry of Culture. It's quite a challenge for this self-taught artist, who doesn't even have his A-levels." I know how to write, but I don't know how to teach, and I never have. It's hard for me to think academically, I've never been taught that ". When he was asked to come to the Collège de France, he was initially surprised. But then he realized that if there's one academic place that's right for him, this would certainly be it." The Collège de France was founded in opposition to the Sorbonne, and its history is a reminder that knowledge does not belong to an elite, but to everyone. In this sense, I feel closer to this school than to the rest of the academic world. " For his opening lecture, Wajdi Mouawad chose to talk about what he knows how to do : write. The playwright also sought to teach that, particularly when it comes to writing, " certain things can't be taught ". He continues : " you can learn to write, but you can't learn to become a poet or a writer. The school will tell you to limit your use of adverbs and adjectives. Yet a writer like Julien Gracq does just the opposite .

What is writing, after all, and how do you know if you're on the right track with a story ? When it comes to writing, Wajdi Mouawad likes to describe himself as " like a tree fed by the tales of the birds that come to populate it "." People ask me how I come up with my stories. I don't. They come to me, like birds landing on tree branches. " A poetic way of saying that in literature as in life, following rules or protocols isn't always enough to tell a good story.

Interview by Emmanuelle Picaud, science journalist